I have another guest post up at The Fictorians today. As a part of their month long look at the business side of writing, I discuss book contract clauses that potentially give publishers rights in your future works. Go take a look at what you need to watch out for before signing that contract.

Monthly Archives: March 2014

Magic and Copyright

A federal court in Nevada published a ruling on Thursday in favor of the magician Teller over a YouTube video showing one of his signature magic tricks, Shadows.

Shadows essentially consists of a spotlight trained on a bud vase containing a rose. The light falls in a such a manner that the shadow of the real rose is projected onto a white screen positioned some distance behind it. Teller then enters the otherwise still scene with a large knife and proceeds to use the knife to dramatically sever the leaves and petals of the rose’s shadow on the screen slowly, one-by-one, whereupon the corresponding leaves of the real rose sitting in the vase fall to the ground, breaking from the stem at exactly the point where Teller cut the shadow projected on the screen behind it.

Penn and Teller both said that no one would figure out how it was accomplished. A Dutch magician Dogge posted a video to YouTube showing himself performing Shadows. He also offered to teach the trick to anyone for around $3,000.

Teller, famous for rarely speaking, was not laughing. He sued for copyright infringement.

But first he’d have to find the rival magician.

Teller went to lengths to punish Dogge for copyright infringement. Literally. Teller had to hire a private investigator to locate Dogge to serve papers to him, and for a while, Dogge evaded service in Belgium, Spain and other European countries. So Teller did a neat new trick. He emailed the court papers to Dogge and managed to convince the judge that his imitator had opened them. It was enough for the judge to allow the lawsuit to proceed. [Hollywood Reporter]

Once he was able to accomplish that trick, the court could give us a ruling on the merits – or at least as much as we can get at the current procedural hurdle.

The judge said that copyright did not protect how the magic trick worked. That would be a utility patent or trade secret if anything. However, the judge did say that pantomimes can be protected by copyright – like any fixed dramatic performance.

Dogge defended himself, among other ways, by claiming that his performance was not substantially similar to Teller’s trick in how the magic part of it worked. In other words, he said it was dissimilar, but only in ways no one watching the trick could see! The judge was less than generous in dealing with this argument:

By arguing that the secret to his illusion is different than Teller’s, Dogge implicitly argues about aspects of the performance that are not perceivable by the audience,” he writes. “In discerning substantial similarity, the court compares only the observable elements of the works in question. Therefore, whether Dogge uses Teller’s method, a technique known only by various holy men of the Himalayas, or even real magic is irrelevant, as the performances appear identical to an ordinary observer.

Teller is not the first magician to sue over the revelation of a trick, but it is not that common. The magic industry, like the comedy industry, relies on industry norms and punishments more frequently than courts or the law. Like comedians who steal material, magicians who reveal tricks are often blackballed from most paying establishments.

Filed under Uncategorized

Copyright Class 9 – Infringement, Part II

This week we look at the second half of the infringement analysis. Well, it’s half if you consider it as one of two elements. However, if we look at how much work or effort you have to put into this, it’s much more than half.

As a brief review, last week’s class set forth the two elements a plaintiff had to prove (beyond owning a valid copyright): 1) copying and 2) improper appropriation. Copying basically means that the defendant actually copied form the plaintiff’s protected work in stead of, say, coming up with the similar work completely independently or copying from a third work from which the plaintiff also copied.

Improper appropriation asks whether what the defendant copied was substantially similar to that part of the plaintiff’s work protected by copyright. Is the allegedly infringing work substantially similar to the copyright protected elements of the plaintiff’s work?

Improper Appropriation – It’s Confusing

Exactly how a court applies or even states this test can vary a great deal depending on what court it is, what medium the works are in, and what the parties argue before the court. It can get pretty murky if you sit down and try to figure out exactly what the test is. Additionally, the actual application of the test is far from a bright line. So when a lawyer equivocates on whether you “can do something” or not without running a foul of copyright, this is one of the main reasons. (Of course, the lack of any bright line rules in Fair Use is the other main reason.)

The famous Judge Learned Hand explained why the test is so hard to nail down in Peter Pan Fabrics v. Martin Weiner Corp, a case involving similar designs printed on fabric:

The test for infringement of a copyright is of necessity vague. In the case of verbal “works” it is well settled that although the “proprietor‘s monopoly extends beyond an exact reproduction of the words, there can be no copyright in the “ideas” disclosed but only in their “expression.” Obviously, no principle can be stated as to when an imitator has gone beyond copying the “idea,” and has borrowed its “expression.” Decisions must therefore inevitably be ad hoc. In the case of designs, which are addressed to the aesthetic sensibilities of an observer, the test is, if possible, even more intangible. No one disputes that the copyright extends beyond a photographic reproduction of the design, but one cannot say how far an imitator must depart from an undeviating reproduction to escape infringement.

Essentially, copyright infringement would be a lot clearer if we said only exact reproductions were infringing. That would make it much easier to predict the outcomes of cases. But we wouldn’t think it was particularly fair if someone could just make a few minor changes and get away with copying the rest? And that wouldn’t really effectuate the goal of providing economic incentives to creators. So, copyright says that a n infringing work does not have to be an exact copy – it only has to be substantially similar. That’s one source of murkiness in the test.

On the other side, we also say that copyright cannot protect ideas; instead, it only protects expressions. So someone can copy ideas without being infringing. But the line between what is an idea and what is expression is itself nearly impossible to nail down.

These two facets, Judge Hand was saying, create the vagueness and uncertainty that surround the infringement test. Take for example two cases that take two completely different approaches: Roth Greeting Cards v. United Card and Satava v. Lowry.

Roth involved two greeting card makers. Roth claimed that United had copied a number of its cards. The short statements on the front and inside of the cards were virtually the same, as was their general placement. The art work was different (generally a cartoonish character under the words on the front of the card). In addressing the improper appropriation element, the court did not try to make a detailed determination of what was protected as expression and what was idea. Note that the words themselves were just phrases or sentences that were too short by themselves to receive copyright protection. It was the selection and arrangement that yielded the originality sufficient for copyright protection.

It appears to us that in total concept and feel the cards of United are the same as the copyrighted cards of Roth. With the possible exception of one United card (exhibit 6), the characters depicted in the art work, the mood they portrayed, the combination of art work conveying a particular mood with a particular message, and the arrangement of the words on the greeting card are substantially the same as in Roth‘s cards. In several instances the lettering is also very similar.

It is true, as the trial court found, that each of United‘s cards employed art work somewhat different from that used in the corresponding Roth cards. However, “The test of infringement is whether the work is recognizable by an ordinary observer as having been taken from the copyrighted source.”

The remarkable similarity between the Roth and United cards in issue (with the possible exception of exhibits 5 and 6) is apparent to even a casual observer. For example, one Roth card (exhibit 9) has, on its front, a colored drawing of a cute moppet suppressing a smile and, on the in- side, the words “i wuv you.” With the exception of minor variations in color and style, defendant‘s card (exhibit 10) is identical. Likewise, Roth‘s card entitled “I miss you already,” depicts a forlorn boy sitting on a curb weeping, with an inside message reading “… and You Haven‘t even Left …” (exhibit 7), is closely paralleled by United‘s card with the same caption, showing a forlorn and weeping man, and with the identical inside message (exhibit 8).

In contrast to the overall impression approach taken by the court in Roth, the court in Satava v. Lowry took a very detailed-oriented approach to the evaluation under the improper appropriation element.

Satava involved two sculptors who made glass sculptures that resemble jellyfish – brightly colored glass inside a cylinder of clear glass. Here the court took great pains to determine what was merely an idea first and then excluded any similarities of ideas from the substantial similarity analysis.

The originality requirement mandates that objective “facts” and ideas are not copyrightable. Similarly, expressions that are standard, stock, or common to a particular subject matter or medium are not protectable under copyright law.

It follows from these principles that no copyright protection may be afforded to the idea of producing a glass-in-glass jellyfish sculpture or to elements of expression that naturally follow from the idea of such a sculpture. Satava may not prevent others from copying aspects of his sculptures resulting from either jellyfish physiology or from their depiction in the glass-in-glass medium.

Satava may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish with tendril-like tentacles or rounded bells, because many jellyfish possess those body parts. He may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish in bright colors, because many jellyfish are brightly colored. He may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish swimming vertically, because jellyfish swim vertically in nature and often are depicted swimming vertically.

Satava may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish within a clear outer layer of glass, because clear glass is the most appropriate setting for an aquatic animal. He may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish “almost filling the entire volume” of the outer glass shroud, because such proportion is standard in glass-in-glass sculpture. And he may not pre- vent others from tapering the shape of their shrouds, because that shape is standard in glass-in-glass sculpture.

Satava‘s glass-in-glass jellyfish sculptures, though beautiful, combine several unprotectable ideas and standard elements. These elements are part of the public domain. They are the common property of all, and Satava may not use copyright law to seize them for his exclusive use.

It is true, of course, that a combination of unprotectable elements may qualify for copyright protection. But it is not true that any combination of unprotectable elements automatically qualifies for copyright protection. Our case law suggests, and we hold today, that a combination of unprotectable elements is eligible for copyright protection only if those elements are numerous enough and their selection and arrangement original enough that their combination constitutes an original work of authorship.

The combination of unprotectable elements in Satava‘s sculpture falls short of this standard. The selection of the clear glass, oblong shroud, bright colors, proportion, vertical orientation, and stereotyped jellyfish form, considered together, lacks the quantum of originality needed to merit copyright protection. These elements are so common- place in glass-in-glass sculpture and so typical of jellyfish physiology that to recognize copyright protection in their combination effectively would give Satava a monopoly on lifelike glass-in-glass sculptures of single jellyfish with vertical tentacles. Because the quantum of originality Satava added in combining these standard and stereotyped elements must be considered “trivial” under our case law, Satava cannot prevent other artists from combining them.

Note that the court did not say that Satava had no copyright in his sculptures; rather, the court said he did not have copyright protection in that which Lowry copied.

We do not mean to suggest that Satava has added nothing copyrightable to his jellyfish sculptures. He has made some copyrightable contributions: the distinctive curls of particular tendrils; the arrangement of certain hues; the unique shape of jellyfishes‘ bells. To the extent that these and other artistic choices were not governed by jellyfish physiology or the glass-in-glass medium, they are original elements that Satava theoretically may protect through copyright law. Satava‘s copyright on these original elements (or their combination) is “thin,” however, comprising no more than his original contribution to ideas already in the public domain. Stated another way, Satava may prevent others from copying the original features he contributed, but he may not prevent others from copying elements of expression that nature displays for all observers, or that the glass-in-glass medium suggests to all sculptors. Satava possesses a thin copyright that protects against only virtually identical copying.

What is of note is that both cases would have come out differently had they used the approach taken by the other. If the Roth court had taken a detail-oriented approach and eliminated all those aspects of the selection and arrangement that are common to most all greeting cards, what might be called functionality-driven ideas, then there would have been nothing left under copyright protection that was copied by United Cards. Conversely, if the Satava court had merely asked whether the two sculptors works shared the same total concept and feel, the court would have concluded that they did.

Improper Appropriation – The Analysis

It basically boils down to two determinations:

- What is protected expression and not unprotected idea?

- Is there substantially similarity between the allegedly infringing work and the expression of the copyrighted work?

Idea/Expression Dichotomy

We talked about the idea/expression dichotomy way back in class 3 when we talked about the Nichols case. We can look at it from two directions. If we take recognized expression, let’s say a novel. Then we start to create greater and greater levels of abstractions from that expression. At some point of abstraction, it will become idea not expression. Taken from the other direction, we can take an idea and start adding more and more details. At some point it will become expression. Of course, where that line is, no one knows.

The quoted portions of the Satava case above are an example of a court looking at the idea/expression dichotomy.

Substantial Similarity

You’ll note that we ran into the term “substantial similarity” last week when we were talking about the copying element. One of the most common ways to prove copying was to do so by inference: showing the defendant had access to the copyright protected work and showing that the allegedly infringing work was substantially similar. From those circumstances, a judge or jury could conclude that copying had occurred.

We see the same words in the improper appropriation analysis, but the test is different. This is one of the frequent sources of confusion. In the copying analysis, we look to dissect the two works as experts would and then ask how similar they are, and we are not concerned about which parts of the copyright protected work are actually protected by copyright.

In contrast, under the improper appropriation analysis, we ask whether certain parts of the two works would be considered substantially similar to an ordinary observer. In Arnstein v. Porter, the court said that the ordinary observer was a lay person. Basically, your average person off the street. However, that was refined, or perhaps clarified, in Dawson v. Hinshaw.

Dawson v. Hinson involved to composers of spirituals, with Dawson accusing Hinshaw Music, among others, of having copied his arrangement of “Ezekial Saw De Wheel.” (The music is linked here.)

As a part of the improper appropriation test, the court said that the ordinary observer should be one who was the intended audience of the work. The court explained how this was what Arnstein case actually stood for, despite its use of the “lay person” language, and how this best served the incentive theory underlying copyright.

Arnstein v. Porter provides the source of modern theory regarding the ordinary observer test. Arnstein involved the alleged infringement of a popular musical composition. Writing for the panel, Judge Jerome Frank first explained that “the plaintiff‘s legally protected interest is not, as such, his reputation as a musician but his interest in the potential financial returns from his compositions which derive from the lay public‘s approbation.” This initial observation gave force to the recognized purpose of the copyright laws of providing creators with a financial incentive to create for the ultimate benefit of the public.

Consistent with its economic incentive view of copyright law, the Arnstein court concluded that “the question, therefore, is whether defendant took from plaintiff‘s works so much of what is pleasing to the ears of lay listeners, who comprise the audience for whom such popular music is composed, that defendant wrongfully appropriated something which belongs to plaintiff.” Thus, under Arnstein, a court should look to the reaction of “lay listeners,” because they comprise the audience of the plaintiff‘s work. The lay listener‘s reaction is relevant because it gauges the effect of the defendant‘s work on the plaintiff‘s market.

Although Arnstein established a sound foundation for the appeal to audience reaction, its reference to “lay listeners” may have fostered the development of a rule that has come to be stated too broadly. Under the facts before it, with a popular composition at issue, the Arnstein court appropriately perceived “lay listeners” and the works‘ “audience” to be the same. However, under Arnstein‘s sound logic, the lay listeners are relevant only because they comprise the relevant audience. Although Arnstein does not address the question directly, we read the case‘s logic to require that where the intended audience is significantly more specialized than the pool of lay listeners, the reaction of the intended audience would be the relevant inquiry. In light of the copyright law‘s purpose of protecting a creator‘s market, we think it sensible to embrace Arnstein‘s command that the ultimate comparison of the works at issue be oriented towards the works‘ intended audience.

To further confuse the matter, how you determine whether it is substantially similar to the intended audience often comes down to the testimony of experts. So you have experts testifying about the technical similarities of the entire work in the first element (copying) while you have experts testifying about what a certain group of people would think about the similarity of certain elements of the works. No room for confusion there at all…

…and that does not even start to take into account when you enter areas like computer software. Read on if you dare – Computer Associates v. Altai.

Filed under Uncategorized

Nancy DiMauro on Reversion Clauses

Friend, writer, and lawyer Nancy DiMauro is over at The Fictorians today telling you what you need to know about reversion clauses.

Okay, let’s look at it this way. I was recently shopping a story to some E-publishers. Before submitting, I checked out the contract terms as stated on the webpage. Buried in the mumbo-jumbo about submission guidelines and other facts was this gem: “Length of grant of publishing rights: Life of copyright.” What the heck?

A copyright lasts your life and another 70 years (in the US and UK. There some other countries which the copyright only lasts 50 years after your death, but it’s still a darned long time.). If you signed a contract with this “reversion” clause your publisher OWNS YOUR STORY for your life, the life of your kids, and a good chunk of your grandchildren’s life. The publisher can do whatever it wants with your story until it has no commercial value (i.e. is in the public domain) and, most likely, not pay you a penny more.

Now do you see the problem?

You might shake your head and say that “well, that was an e-publisher, the traditional houses aren’t like that.” Oh yes, they can be. If you let them. Publishers of all kinds are trying to grab as many of your right as possible, keep them for as long as possible and return as few of them to you as possible. This doesn’t make the publishers “evil.” It just means they are better at looking out for their businesses interests than most writers are. After all, they make money off the stories other people write. Of course, the publisher wants to keep those words for as long as possible.

“But wait!” you say. “Isn’t there something about my getting the rights back if the work goes out of print?”

Yep. That’s the reversion clause. And Nancy goes on to tell you what you need to make sure is in there to avoid getting burned.

Filed under Uncategorized

Copyright Class 8 – Infringement, Part 1

This week we move into a complicated topic – copyright infringement. This one will be a multi-class topic. The law on the second element of infringement, which we will take up next week, is one of the more confusing and confused parts of copyright law.

We have three cases this week, all involving music. First up is a classic case from the 1940’s, Arnstein v. Porter. That case sets up the two elements of proving infringement: copying and improper appropriation. Then we have two cases examining the first element, copying: Selle v. Gibb and Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs Music, Inc.

The Basic Infringement Analysis – Arnstein v. Porter

Ira Arnstein sued Cole Porter claiming that a number of songs recorded by Porter infringed the copyright in a number of Arnstein’s musical works. The Second Circuit, in reviewing the decision of the lower court, set out the two elements a plaintiff needs to prove to make a case for copyright infringement.

[I]t is important to avoid confusing two separate elements essential to a plaintiff’s case in such a suit: (a) that defendant copied from the plaintiff’s copyrighted work and (b) that the copying (assuming it to be proved) went so far as to constitute improper appropriation.

So, a copyright owner has to prove that the defendant copied from the plaintiff’s protected work and that what the defendant copied was protected by copyright.

The easiest way to understand the reason you have to separately show copying is to understand what is not copying and therefore not infringement. It is not copying if the defendant came up with the allegedly infringing work on their own without copying (consciously or unconsciously from the plaintiff’s work), even if the two works are identical. That is a maxim of copyright law, though we will see that a defendant whose work is strikingly similar to a plaintiff’s work may have difficulties even if he came up with the work on his own. A court won’t disregard the need to find the copying occurred, but if the two works are identical, the court may have a hard time believing that the defendant did not copy the plaintiff’s work.

Another way in which two works might be very similar and yet not have resulted from one copying the other is if both the plaintiff’s work and the defendant’s work were copied from the same third source. If the plaintiff copied from an older work and the defendant copied from the same old work, the two resulting works could be very similar and yet the defendant did not copy the plaintiff’s work.

Copying can be established either by showing direct or indirect evidence of copying. Direct evidence might be an admission by the defendant, testimony of third parties who witnessed the copying, or some other proof. We saw one other way in Feist v. Rural Telephone Co a few weeks ago. Rural Telephone had inserted a few fake names and numbers in their telephone book in order to detect copying.

Indirect evidence involves the court drawing an inference that copying occurred from circumstantial evidence. Basically, if the plaintiff can show that the defendant had access to the work and that there is substantial similarity between the plaintiff’s work and the defendant’s work, then the court can infer copying took place. The defendant can rebut such an inference by introducing evidence of how the work was created independently.

More controversially, the Arnstein court said that even in the absence of any evidence of access to the plaintiff’s protected work, the inference of copying can still be made if the two works are strikingly similar. Other courts frequently recite this possibility but some courts have said that there needs to be some evidence of access, with the strength of the access evidence varying conversely with the needed level of similarity. Selle v. Gibb takes up this issue.

The improper appropriation element asks a different question. Once the plaintiff has established that the defendant copied form the plaintiff’s work, the plaintiff still has to prove that what the defendant copied is something protected by copyright. For example, ideas are not protected by copyright. So a defendant could admit to stealing the ideas from the plaintiff’s work without having to worry about infringing the plaintiff’s rights under copyright. We’ll look at this element in more detail next week.

Copying – Selle v. Gibb and Bright Tunes Music v Harrisong Music

Selle maintained that the Bee Gee’s song “How Deep Is Your Love” infringed his song “Let It End” (listen for yourself). Selle brought in an expert, a professor of music, who testified about the similarity of the two songs.

According to Dr. Parsons’ testimony, the first eight bars of each song (Theme A) have twenty-four of thirty-four notes in plaintiff’s composition and twenty-four of forty notes in defendants’ composition which are identical in pitch and symmetrical position. Of thirty-five rhythmic impulses in plaintiff’s composition and forty in defendants’, thirty are identical. In the last four bars of both songs (Theme B), fourteen notes in each are identical in pitch, and eleven of the fourteen rhythmic impulses are identical. Both Theme A and Theme B appear in the same position in each song but with different intervening material.

Dr. Parsons testified that, in his opinion, “the two songs had such striking similarities that they could not have been written independent of one another.” He also testified that he did not know of two songs by different composers “that contain as many striking similarities” as do the two songs at issue here. However, on several occasions, he declined to say that the similarities could only have resulted from copying.

Despite what might have qualified as striking similarity, the trial judge overturned a jury verdict in the plaintiff’s favor because the judge said that the plaintiff had not met their burden of proof on the element of copying. More specifically, the judge said that they needed some proof that the defendants had access to the plaintiff’s song, something that extended beyond mere speculation or conjecture.

As a threshold matter, therefore, it would appear that there must be at least some other evidence which would establish a reasonable possibility that the complaining work was available to the alleged infringer. As noted, two works may be identical in every detail, but, if the alleged infringer created the accused work independently or both works were copied from a common source in the public domain, then there is no infringement. Therefore, if the plaintiff admits to having kept his or her creation under lock and key, it would seem logically impossible to infer access through striking similarity. Thus, although it has frequently been written that striking similarity alonecan establish access, the decided cases suggest that this circumstance would be most unusual. The plaintiff must always present sufficient evidence to support a reasonable possibility of access because the jury cannot draw an inference of access based upon speculation and conjecture alone.

…

In granting the defendants’ motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict, Judge Leighton relied primarily on the plaintiff’s failure to adduce any evidence of access and stated that an inference of access may not be based on mere conjecture, speculation or a bare possibility of access. 567 F.Supp. at 1181. Thus, in Testa v. Janssen, 492 F.Supp. 198, 202-03 (W.D.Pa. 1980), the court stated that “[t]o support a finding of access, plaintiffs’ evidence must extend beyond mere speculation or conjecture. And, while circumstantial evidence is sufficient to establish access, a defendant’s opportunity to view the copyrighted work must exist by a reasonable possibility — not a bare possibility” (citation omitted).

It should also be noted that the Bee Gee’s introduced quite a bit of testimony about the process by which they created their song “How Deep Is Your Love.”

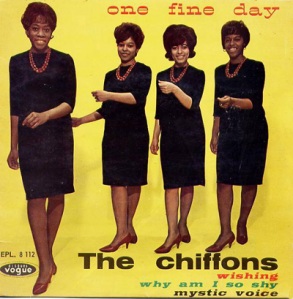

In Bright Tunes, the plaintiff claimed the that George Harrison’s song “My Sweet Lord” infringed “He’s So Fine” composed by Ronald Mack and recorded by The Chiffons.

Here, unlike Selle’s “Let It End”, The Chiffon’s “He’s So Fine” enjoyed quite a bit of popular success. It was #1 in America for a time and was a top hit in England as well. So access was easily established. Substantial similarity was also shown fairly easily. The main import of this particular case is that the court accepted that George Harrison did not intentionally or consciously copy “He’s So Fine.” The court accepted Harrison’s proffered description of how he wrote and composed “My Sweet Lord.” However, the court said it did not matter that the copying was unconscious; it still satisfied that element of the copyright infringement analysis.

What happened? I conclude that the composer, in seeking musical materials to clothe his thoughts, was working with various possibilities. As he tried this possibility and that, there came to the surface of his mind a particular combination that pleased him as being one he felt would be appealing to a prospective listener; in other words, that this combination of sounds would work. Why? Because his subconscious knew it already had worked in a song his conscious mind did not remember. Having arrived at this pleasing combination of sounds, the recording was made, the lead sheet prepared for copyright and the song became an enormous success. Did Harrison deliberately use the music of He’s So Fine? I do not believe he did so deliberately. Nevertheless, it is clear that My Sweet Lord is the very same song as He’s So Fine with different words, and Harrison had access to He’s So Fine. This is, under the law, infringement of copyright, and is no less so even though subconsciously accomplished.

Next week – Improper Appropriation

So copying is the first element that must be shown. Well technically you have to show ownership of a valid copyright first, but once that is done, the court moves on to the two step infringement analysis. Once copying is established the next step in the analysis is to prove improper appropriation. Next week!

Filed under Uncategorized

A Second Guest Post – The Basics of Copyright

I have a second guest post up today on The Fictorians. It covers, as the title suggests, the basics of copyright.

Filed under Uncategorized

Guest Post on Fictorians – What is IP?

Today, I have a guest post up on The Fictorians entitled Intellectual Property – What is it? First, it relates how lawyers conceptualize property, including property in objects of the mind – in other words, intellectual property. Then it gives a brief description of the major types of IP.

Filed under Uncategorized

Copyright Class 7 – Work For Hire

Last week we looked at one special type of authorship, joint authorship. This week, we will be examining the other special type of authorship, work for hire. This is one of areas of copyright that I see misused or misstated quite often.

What is a Work For Hire?

Section 101 of the Copyright Act provides two ways that a work can be a work for hire (or work made for hire in the Act’s terminology):

A “work made for hire” is—

(1) a work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment; or

(2) a work specially ordered or commissioned for use as a contribution to a collective work, as a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, as a translation, as a supplementary work, as a compilation, as an instructional text, as a test, as answer material for a test, or as an atlas, if the parties expressly agree in a written instrument signed by them that the work shall be considered a work made for hire. For the purpose of the foregoing sentence, a “supplementary work” is a work prepared for publication as a secondary adjunct to a work by another author for the purpose of introducing, concluding, illustrating, explaining, revising, commenting upon, or assisting in the use of the other work, such as forewords, afterwords, pictorial illustrations, maps, charts, tables, editorial notes, musical arrangements, answer material for tests, bibliographies, appendixes, and indexes, and an “instructional text” is a literary, pictorial, or graphic work prepared for publication and with the purpose of use in systematic instructional activities.

An Employee Within the Scope of His or Her Employment

Let’s consider the first means – a work created by “an employee within the scope of his or her employment.” For many years, courts developed their own tests specifically for this area of copyright. They focused on whether the hiring party had the right to control or actually controlled aspects of the creation of the work. However, the Supreme Court swept these aside in our primary case for today’s class, CCNV v. Reid (oral arguments).

The Community for Creative Non-Violence, an organization devoted to combatting homelessness, made the decision to commission a sculpture:

Snyder and fellow CCNV members conceived the idea for the nature of the display: a sculpture of a modern Nativity scene in which, in lieu of the traditional Holy Family, the two adult figures and the infant would appear as contemporary homeless people huddled on a streetside steam grate. The family was to be black (most of the homeless in Washington being black); the figures were to be life-sized, and the steam grate would be positioned atop a platform “pedestal,” or base, within which special effects equipment would be enclosed to emit simulated “steam” through the grid to swirl about the figures. They also settled upon a title for the work — “Third World America” — and a legend for the pedestal: “and still there is no room at the inn.”

Snyder, on behalf of CCNV, began to negotiate with a Baltimore-based sculptor, James Earl Reid.

In the course of two telephone calls, Reid agreed to sculpt the three human figures. CCNV agreed to make the steam grate and pedestal for the statue. Reid proposed that the work be cast in bronze, at a total cost of approximately $100,000 and taking six to eight months to complete. Snyder rejected that proposal because CCNV did not have sufficient funds, and because the statue had to be completed by December 12 to be included in the pageant. Reid then suggested, and Snyder agreed, that the sculpture would be made of a material known as “Design Cast 62,” a synthetic substance that could meet CCNV’s monetary and time constraints, could be tinted to resemble bronze, and could withstand the elements. The parties agreed that the project would cost no more than $15,000, not including Reid’s services, which he offered to donate. The parties did not sign a written agreement. Neither party mentioned copyright.

After Reid received an advance of $3,000, he made several sketches of figures in various poses. At Snyder’s request, Reid sent CCNV a sketch of a proposed sculpture showing the family in a creche-like setting: the mother seated, cradling a baby in her lap; the father standing behind her, bending over her shoulder to touch the baby’s foot. Reid testified that Snyder asked for the sketch to use in raising funds for the sculpture. Snyder testified that it was also for his approval. Reid sought a black family to serve as a model for the sculpture. Upon Snyder’s suggestion, Reid visited a family living at CCNV’s Washington shelter, but decided that only their newly born child was a suitable model. While Reid was in Washington, Snyder took him to see homeless people living on the streets. Snyder pointed out that they tended to recline on steam grates, rather than sit or stand, in order to warm their bodies. From that time on, Reid’s sketches contained only reclining figures.

Throughout November and the first two weeks of December, 1985, Reid worked exclusively on the statue, assisted at various times by a dozen different people who were paid with funds provided in installments by CCNV. On a number of occasions, CCNV members visited Reid to check on his progress and to coordinate CCNV’s construction of the base. CCNV rejected Reid’s proposal to use suitcases or shopping bags to hold the family’s personal belongings, insisting instead on a shopping cart. Reid and CCNV members did not discuss copyright ownership on any of these visits.

On December 24, 1985, 12 days after the agreed-upon date, Reid delivered the completed statue to Washington. There it was joined to the steam grate and pedestal prepared by CCNV, and placed on display near the site of the pageant. Snyder paid Reid the final installment of the $15,000. The statue remained on display for a month.

The statue was then returned to the sculptor for minor repairs. At that point, the relationship between the two parties began to sour. CCNV asked for the sculpture to be returned to them so that they could take it on a multi-city tour. Reid refused, claiming that the sculpture had not been made to withstand such a tour. The eventual result was the litigation between the parties that made its way all the way to the Supreme Court.

Reid argued that he owned the copyright in the statue. He sculpted it after all. CCNV argued that they owned the copyright because the sculpture was a work for hire. CCNV could not argue that it was a work for hire under the second definition in 101 because there was no contract and because a sculpture was not one of the specific types of works listed in the second definition that could be converted into a work for hire by a contract. So instead, they argued that Reid had created the sculpture as an employee acting within the scope of his employment.

The Supreme Court rejected CCNV’s claim and in the course of doing so also established the legal rule for making a determination under the first work for hire definition. Previously, lower courts had developed special tests (right to control, actual control) for figuring out when a work was created by “an employee within the scope of his or her employment.” The Supreme Court rejected those tests, holding instead that the determination was made by “using principles of the general common law of agency, [to ascertain] whether the work was prepared by an employee or an independent contractor.”

The Court identified a number of factors a court should consider in making that determination:

In determining whether a hired party is an employee under the general common law of agency, we consider the hiring party’s right to control the manner and means by which the product is accomplished. Among the other factors relevant to this inquiry are the skill required; the source of the instrumentalities and tools; the location of the work; the duration of the relationship between the parties; whether the hiring party has the right to assign additional projects to the hired party; the extent of the hired party’s discretion over when and how long to work; the method of payment; the hired party’s role in hiring and paying assistants; whether the work is part of the regular business of the hiring party; whether the hiring party is in business; the provision of employee benefits; and the tax treatment of the hired party.

The list is non-exhaustive and no single factor is determinative. A court evaluates each factor under the given facts of a particular case and then makes an overall determination of whether the creator is an employee or an independent contractor. (The Restatement cited by the Court actually uses the terminology of “Master” and “Servant” rather than “Employer” and “Employee.” Those are just very old terms, not a reference to a Depeche Mode song.)

After examine each of these factors, the Court determined that Reid was an independent contractor, and that therefore, the sculpture was not a work for hire.*

Because they did not find him to be an employee, the Court did not have to go on to discuss the second half of the definition. If the creator of the work is an employee, the work still has to have been created within the scope of the creator’s employment in order to be considered a work for hire. Consider this, if you work a full-time job unrelated to writing, you are an employee, right? Would you consider everything you write at night and on weekends while employed as a work for hire just because you are an employee? No, you wouldn’t. While you are an employee, you are not writing those works of authorship within the scope of your employment.

The determination under the second half of the first definition (“within the scope of his or her employment”) is also based on general principles of agency law. A work is created within the scope of the employees work if “(a) [the act of creation] is of the kind he is employed to perform; (b) it occurs substantially within the authorized time and space limits; [and] (c) it is actuated, at least in part, by a purpose to serve the [employer].” (Restatement (Second) of Agency, Section 228)

Specially Commissioned Works

Here’s the second way in which a work can be a work for hire (just so you don’t have to scroll ALL the way back up there to re-read it):

(2) a work specially ordered or commissioned for use as a contribution to a collective work, as a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, as a translation, as a supplementary work, as a compilation, as an instructional text, as a test, as answer material for a test, or as an atlas, if the parties expressly agree in a written instrument signed by them that the work shall be considered a work made for hire. For the purpose of the foregoing sentence, a “supplementary work” is a work prepared for publication as a secondary adjunct to a work by another author for the purpose of introducing, concluding, illustrating, explaining, revising, commenting upon, or assisting in the use of the other work, such as forewords, afterwords, pictorial illustrations, maps, charts, tables, editorial notes, musical arrangements, answer material for tests, bibliographies, appendixes, and indexes, and an “instructional text” is a literary, pictorial, or graphic work prepared for publication and with the purpose of use in systematic instructional activities.

The definition also requires a signed contract, but that signed written instrument can actually come later as long as the initial agreement was for a work for hire arrangement. It also can only be used to create work for hire status for certain specified types of works.

We should immediately notice that merely saying a work will be a work for hire in a contract only works for very limited types of works enumerated in (2). That is contrary to my impression of the common belief among writers and other creatives that a contract can always make something a work for hire. I believe, though it is difficult for me to verify, that this may also be contrary to common practices in the publishing industry. I suspect that there are a lot of contracts out there that specify that a book is a work for hire and that most everyone involved believes those books are works for hire.

But they are probably are not.

Can you imagine a novel written under conditions that would meet the first definition (“employee within scope of his or her employment”)? Almost everyone of the factors would go in favor of the writer being an independent contractor. And novels do not appear to fall under any of enumerated categories of works that fall under the second definition that allows work for hire status to be created by contract.

Now even if that is the case, it does not make a huge difference. I’m also pretty sure a court looking at those contracts would interpret them as a complete transfer of the copyright even though it was an unsuccessful attempt to make the book a work for hire. There is so much built up understanding in the publishing industry about what comes with work for hire status, that a court might be willing to interpret the contract in light of that common understanding.

Additionally, many contracts contain a savings clause that says just that – that in the event a court finds the work not to be a work made for hire, then the contract will act as a complete transfer. The notable difference between a work for hire and a complete transfer is termination rights (see below).

The Result of a Work Being a Work For Hire

Section 201 of the Copyright Act details who owns a copyright. Generally, as provided in 201(a), copyright vests in the author of the work. However, 201(b) specifies that if the work is a work for hire, then the hiring party is considered the author, and thus the copyright vests in the hiring party initially. In other words, a work for hire is not a transfer of copyright rights. Instead, it defines who the author is for copyright purposes.

To understand what that means, let’s compare a book written as a work for hire with a non-work for hire book in which the entire copyright has been transferred away. Any transfer of copyright, including a transfer on the entire copyright for its entire duration, can be terminated unilaterally by the author after a specified period of time (35 years for works created today). You can get it back. If, however, the work is a work for hire, you as the writer are not considered the author; you have no termination rights.

*As an aside, note that this conclusion reached by the Supreme Court did not appear to resolve the dispute. It looks like the parties were arguing about the wrong set of rights the entire time – all the way to the Supreme Court! Recall that what CCNV wanted was to take the physical embodiment of the work of authorship, i.e. the sculpture itself, on tour. That’s not a copyright issue. Who owns the sculpture itself is matter of personal property law. Maybe there was more to the situation not made apparent in the litigation, but if not, it’s a potentially a bit embarrassing for the lawyers involved.

Filed under Uncategorized