This week we move into a complicated topic – copyright infringement. This one will be a multi-class topic. The law on the second element of infringement, which we will take up next week, is one of the more confusing and confused parts of copyright law.

We have three cases this week, all involving music. First up is a classic case from the 1940’s, Arnstein v. Porter. That case sets up the two elements of proving infringement: copying and improper appropriation. Then we have two cases examining the first element, copying: Selle v. Gibb and Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs Music, Inc.

The Basic Infringement Analysis – Arnstein v. Porter

Ira Arnstein sued Cole Porter claiming that a number of songs recorded by Porter infringed the copyright in a number of Arnstein’s musical works. The Second Circuit, in reviewing the decision of the lower court, set out the two elements a plaintiff needs to prove to make a case for copyright infringement.

[I]t is important to avoid confusing two separate elements essential to a plaintiff’s case in such a suit: (a) that defendant copied from the plaintiff’s copyrighted work and (b) that the copying (assuming it to be proved) went so far as to constitute improper appropriation.

So, a copyright owner has to prove that the defendant copied from the plaintiff’s protected work and that what the defendant copied was protected by copyright.

The easiest way to understand the reason you have to separately show copying is to understand what is not copying and therefore not infringement. It is not copying if the defendant came up with the allegedly infringing work on their own without copying (consciously or unconsciously from the plaintiff’s work), even if the two works are identical. That is a maxim of copyright law, though we will see that a defendant whose work is strikingly similar to a plaintiff’s work may have difficulties even if he came up with the work on his own. A court won’t disregard the need to find the copying occurred, but if the two works are identical, the court may have a hard time believing that the defendant did not copy the plaintiff’s work.

Another way in which two works might be very similar and yet not have resulted from one copying the other is if both the plaintiff’s work and the defendant’s work were copied from the same third source. If the plaintiff copied from an older work and the defendant copied from the same old work, the two resulting works could be very similar and yet the defendant did not copy the plaintiff’s work.

Copying can be established either by showing direct or indirect evidence of copying. Direct evidence might be an admission by the defendant, testimony of third parties who witnessed the copying, or some other proof. We saw one other way in Feist v. Rural Telephone Co a few weeks ago. Rural Telephone had inserted a few fake names and numbers in their telephone book in order to detect copying.

Indirect evidence involves the court drawing an inference that copying occurred from circumstantial evidence. Basically, if the plaintiff can show that the defendant had access to the work and that there is substantial similarity between the plaintiff’s work and the defendant’s work, then the court can infer copying took place. The defendant can rebut such an inference by introducing evidence of how the work was created independently.

More controversially, the Arnstein court said that even in the absence of any evidence of access to the plaintiff’s protected work, the inference of copying can still be made if the two works are strikingly similar. Other courts frequently recite this possibility but some courts have said that there needs to be some evidence of access, with the strength of the access evidence varying conversely with the needed level of similarity. Selle v. Gibb takes up this issue.

The improper appropriation element asks a different question. Once the plaintiff has established that the defendant copied form the plaintiff’s work, the plaintiff still has to prove that what the defendant copied is something protected by copyright. For example, ideas are not protected by copyright. So a defendant could admit to stealing the ideas from the plaintiff’s work without having to worry about infringing the plaintiff’s rights under copyright. We’ll look at this element in more detail next week.

Copying – Selle v. Gibb and Bright Tunes Music v Harrisong Music

Selle maintained that the Bee Gee’s song “How Deep Is Your Love” infringed his song “Let It End” (listen for yourself). Selle brought in an expert, a professor of music, who testified about the similarity of the two songs.

According to Dr. Parsons’ testimony, the first eight bars of each song (Theme A) have twenty-four of thirty-four notes in plaintiff’s composition and twenty-four of forty notes in defendants’ composition which are identical in pitch and symmetrical position. Of thirty-five rhythmic impulses in plaintiff’s composition and forty in defendants’, thirty are identical. In the last four bars of both songs (Theme B), fourteen notes in each are identical in pitch, and eleven of the fourteen rhythmic impulses are identical. Both Theme A and Theme B appear in the same position in each song but with different intervening material.

Dr. Parsons testified that, in his opinion, “the two songs had such striking similarities that they could not have been written independent of one another.” He also testified that he did not know of two songs by different composers “that contain as many striking similarities” as do the two songs at issue here. However, on several occasions, he declined to say that the similarities could only have resulted from copying.

Despite what might have qualified as striking similarity, the trial judge overturned a jury verdict in the plaintiff’s favor because the judge said that the plaintiff had not met their burden of proof on the element of copying. More specifically, the judge said that they needed some proof that the defendants had access to the plaintiff’s song, something that extended beyond mere speculation or conjecture.

As a threshold matter, therefore, it would appear that there must be at least some other evidence which would establish a reasonable possibility that the complaining work was available to the alleged infringer. As noted, two works may be identical in every detail, but, if the alleged infringer created the accused work independently or both works were copied from a common source in the public domain, then there is no infringement. Therefore, if the plaintiff admits to having kept his or her creation under lock and key, it would seem logically impossible to infer access through striking similarity. Thus, although it has frequently been written that striking similarity alonecan establish access, the decided cases suggest that this circumstance would be most unusual. The plaintiff must always present sufficient evidence to support a reasonable possibility of access because the jury cannot draw an inference of access based upon speculation and conjecture alone.

…

In granting the defendants’ motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict, Judge Leighton relied primarily on the plaintiff’s failure to adduce any evidence of access and stated that an inference of access may not be based on mere conjecture, speculation or a bare possibility of access. 567 F.Supp. at 1181. Thus, in Testa v. Janssen, 492 F.Supp. 198, 202-03 (W.D.Pa. 1980), the court stated that “[t]o support a finding of access, plaintiffs’ evidence must extend beyond mere speculation or conjecture. And, while circumstantial evidence is sufficient to establish access, a defendant’s opportunity to view the copyrighted work must exist by a reasonable possibility — not a bare possibility” (citation omitted).

It should also be noted that the Bee Gee’s introduced quite a bit of testimony about the process by which they created their song “How Deep Is Your Love.”

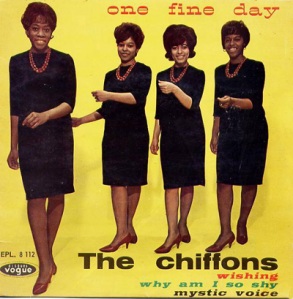

In Bright Tunes, the plaintiff claimed the that George Harrison’s song “My Sweet Lord” infringed “He’s So Fine” composed by Ronald Mack and recorded by The Chiffons.

Here, unlike Selle’s “Let It End”, The Chiffon’s “He’s So Fine” enjoyed quite a bit of popular success. It was #1 in America for a time and was a top hit in England as well. So access was easily established. Substantial similarity was also shown fairly easily. The main import of this particular case is that the court accepted that George Harrison did not intentionally or consciously copy “He’s So Fine.” The court accepted Harrison’s proffered description of how he wrote and composed “My Sweet Lord.” However, the court said it did not matter that the copying was unconscious; it still satisfied that element of the copyright infringement analysis.

What happened? I conclude that the composer, in seeking musical materials to clothe his thoughts, was working with various possibilities. As he tried this possibility and that, there came to the surface of his mind a particular combination that pleased him as being one he felt would be appealing to a prospective listener; in other words, that this combination of sounds would work. Why? Because his subconscious knew it already had worked in a song his conscious mind did not remember. Having arrived at this pleasing combination of sounds, the recording was made, the lead sheet prepared for copyright and the song became an enormous success. Did Harrison deliberately use the music of He’s So Fine? I do not believe he did so deliberately. Nevertheless, it is clear that My Sweet Lord is the very same song as He’s So Fine with different words, and Harrison had access to He’s So Fine. This is, under the law, infringement of copyright, and is no less so even though subconsciously accomplished.

Next week – Improper Appropriation

So copying is the first element that must be shown. Well technically you have to show ownership of a valid copyright first, but once that is done, the court moves on to the two step infringement analysis. Once copying is established the next step in the analysis is to prove improper appropriation. Next week!

Pingback: Copyright Class 10 Infringement Part III | Writer-in-Law